“King Harald’s Saga” by Judith Weir

King Harald's Saga is a grand opera in three acts by Judith Weir, (b. 1954) one of England’s leading composers. She is most well known for her operas A Night at the Chinese Opera, The Vanishing Bridegroom and Blond Eckbert, though she has also been internationally recognized for her chamber and orchestral works. From a young age, Weir was inspired by the works of Webern, Cage, Berg, Stravinsky and Bartok. In a 2005 interview, she recalls the start of her career as a composer:

“The first time I felt I’d written a piece which was really something was my piece for [soprano] Jane Manning called King Harald’s Saga, which I wrote when I was 24. I think the reason that has stayed in my memory was because of her: she was so enthusiastic, whereas previously it had been my own enthusiasm that had kept me going.”

This work, scored for solo soprano, lasts only for about 12 minutes and features eight different roles, including a chorus. Each character has a particular style or musical theme, such as the inverted intervals for Harald’s wives or St. Olaf’s long sweeping lines that create a ghastly, ethereal effect. Based on the collection of Norse mythology tales Heimskringla by Snorri Sturluson, the Icelandic poet and historian, the plot centers around King Harald I Fairhair. He was the first king of Norway, who died nineteen days before the Battle of Hastings in 1066 AD. Harald is characterized as a ruthless, and clearly disturbed, king who will stop at nothing to expand his kingdom. Other characters include Tostig, whose slippery and manipulative nature is portrayed in a snakelike Ab Ionian melody; St. Olaf, who sings in a chant-like fashion to match his holiness; the Norwegian army and a Soldier, who mimic Harald’s rhythm motives; and the Icelandic sage who calmly presents the moral of the story in F Ionian.

Rhythm

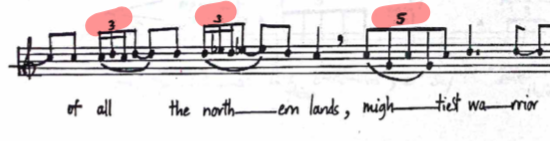

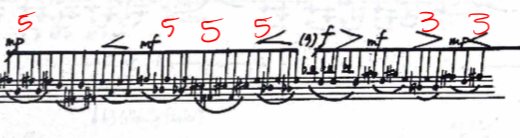

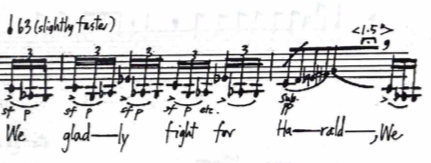

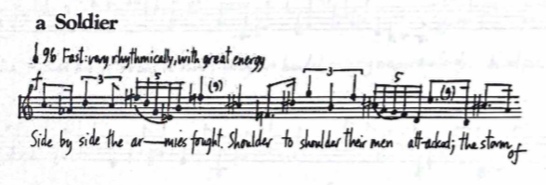

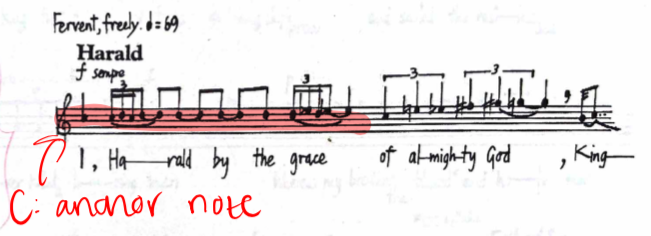

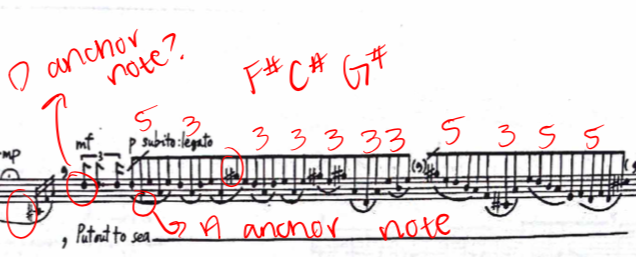

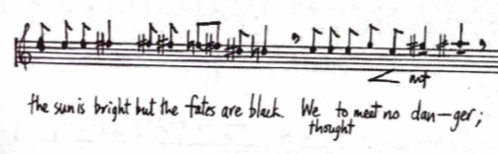

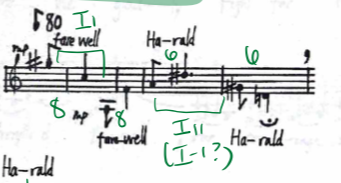

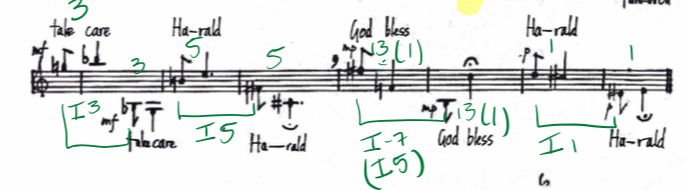

A main aspect of the music that shows which characters are acting with or against Harold is the rhythm. King Harold’s main rhythmic motive always includes a triplet or quintuplet figure, surrounded by syncopated eighths. His opening theme is full of these rhythms as he is creating his own fanfare to celebrate his various triumphs in battle; the motive appears eleven times in the first three pages (see Figure 1). Similarly, in the second act, Harald’s theme of triplets and quintuplets continues in the groupings of pitches during his voyage to England (see Figure 2). The Norwegian army mimics Harald’s rhythmic intensity in a much more aggressive manner. Not only is their section marked as “rough” (as opposed to Harald’s sections that are freer and legato), the lower register in which the singer must perform requires that they sing in almost an “unpolished” way (see Figure 3). Finally, the Soldier who recounts the final battle delivers the narration “very rhythmically, with great energy” (see Figure 4). Featuring triplet and quintuplets that break up the melodic line, this section is filled with the tension of war.

Figure 1: Harald’s opening rhythms

Figure 2: Harald’s second act rhythms

Figure 3: Norwegian army’s rhythm

Figure 4: Soldier’s rhythm

In contrast, the other characters who oppose Harold have languid and legato rhythms. Tostig and Olaf’s material continues the theme of note groupings, featuring triplets, quadruplets, and quintuplets. However, these melodies are delivered in a fluid manner, often with ample time for breathing.

Pitch: Anchor Notes and Modes

This piece also features a series of anchor notes throughout the melodic material, cementing the characters into their own modalities. In the opening section, King Harald’s anchor note is C, often followed in succession by D and Eb (see Figure 5). The regular appearance of Eb and Ab suggests that the opening is in C Aeolian (with a raised seventh scale degree). Much of the army’s melodic material is also in C Aeolian (see Figure 2), mimicking Harald’s anchor note of C. Harald’s second section features the anchor note D, although A is also heavily featured; considering the fact that the melodic material contains F#, C#, and G#, one could make the argument that the true anchor note is A, pushing the modality into A Ionian. However, I argue that this section is centered around D, especially because of the opening two bars that present a sort of fanfare on D5 (see Figure 6). Because of the presence of G#, this would make the mode D Lydian. Mimicking this section is the Messenger, whose melodic content also surrounds D5 and operates within the D Lydian scale (see Figure 7).

Figure 5: Harald’s opening melodic material

Figure 6: Harald’s second act melodic material

Figure 7: Messenger’s melodic material

Pitch: Inverted Intervals

A notable part of the piece is in the second act with the only women in the show. The soprano sings into two different registers to portray singing a duet; they perform a series of inverted intervals. First, one wife sings G#5 down to C5, and the other responds with A3 up to F4. Both intervals have a span of 8 semitones. Next, they sing inverted intervals spanning 6 semitones. As the sequence continues, there are a few instances during which the span of semitones is the same amount of semitones as the inverted transposition.

Figure 8: Wives’ inverted intervals

Moral

It’s clear that Judith Weir has an incredible grasp on the sound of the high female voice, and bestows a stunning amount of interpretive freedom to the performer. As music critic Timothy Mangan wrote:

“Weir’s opera effectively conjures a feeling of time and place, the singer taking all roles and mellifluous music slipping quickly high and low: The soprano is both bard and siren.”

But such a unique piece in this format begs the question: why this source material for the soprano voice? Considering most of the characters are men, and the moral of the saga is about the harmful actions of said men, why choose the female voice to be the medium of storytelling? I propose that as Weir herself continues to assert her presence in the field of music composition, she asserts the female voice into a story centered around men, giving the most notable melodic material to the only women in the show. As Susan McClary remarks about the presence of feminism in music:

“Feminism has been very late in making an appearance in music criticism, and this is largely owing to the success composers, musicologists, and theorists have had in maintaining the illusion that music is an entirely autonomous realm. But the gender politics which assign prestige to ‘masculinity’ mark the emergence of modernism in music as much as in the other arts.”

In Weir’s telling of the story, masculinity is not celebrated, but punished. The wise sage in the epilogue could certainly be characterized as a woman (although not explicitly stated); by making a woman the narrator, the sage and singer become one. The moral of the piece is delivered directly in the epilogue: war always brings death, destruction and mourning into the world, and there is always a better way. The challenge presented by the sage is if we can find that better way to move forward.